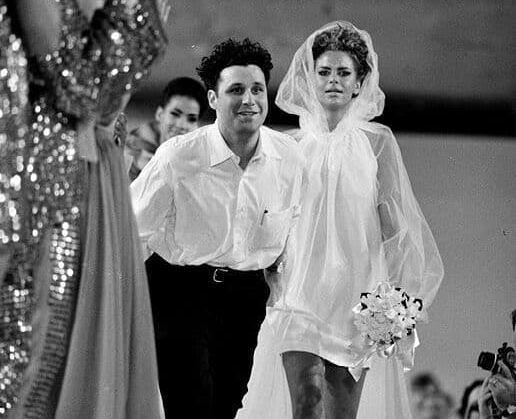

FROM THE ISSUE: RICK OWENS, GOTH ROYALTY

Inside Issue 21, Anders Christian Madsen writes about Rick Owens: goth royalty.

Terrifying as it is to revisit one’s own work, there are few things I won’t do for my friends at 10. (I could list examples but Sophia has asked me to keep it PG.) So, when I was invited to write a story charting my history with Rick Owens, I went back to our very first interview – an email affair from 2010 – and discovered this treasure: “Over the past decade you have gone from being a fashion designer to a ‘fashion designer and personality/icon’,” 23-year-old Anders observed

“In years to come, do you see yourself becoming a Lagerfeld-like, superhuman type of character?”, I asked him. Writing in his signature all-caps, Rick replied: “I’M FLATTERED THAT YOU THINK I COULD MAINTAIN THAT KIND OF INTEREST. I DON’T THINK I HAVE THAT MUCH ENERGY.”

A decade on, wouldn’t you know it, I’ve emerged as something of a prophet. In the fleeting world of post-digital fashion culture, Owens has manifested as one of the most permanent phenomena in the industry. And in a creative climate where the artistic directors of the grandes maisons come and go and the genetics of houses can transform in a season, Rick Owens and the brand that carries his name have become enduring symbols of cool, of avant-garde, of intelligence: an icon who stays true to his own tastes and values without ever losing his drive or his touch with the current. In fact, his statements – both material and vocal – often feel ahead, far ahead, of the curve.

Backstage, before his men’s show this January, he encapsulated the constancy that creates the base for this endurance. “These are things we’ve all seen from me before, but when things are a good idea, I think they’re worth repeating,” he said, referring to a collection that served as a reminder of all the Rick forever-pieces you want to own but haven’t acquired yet. “The idea of redeveloping motifs that are part of your signature, I think that’s a good thing to put out there: the idea of not letting things become disposable, which is all too often the case.”

It’s true that Owens’ work evolves slowly within a very defined aesthetic, but contrary to other designers about whom you could say the same, his seasonal expressions are fuelled by so much emotion – so much awareness for the world that surrounds him – that we feel the progress he makes. When, like in January, he raises his models up on an elevated runway and puts them in sky-high platforms so they tower over us like imposing giants in capes, it’s a move that’s reflective of in his own psychological state. In this particular case, it felt like his literal way of putting the world into perspective. As he wrote in his self-penned show notes, reflecting on a recent trip to the pyramids: “MEASURING THE INSIGNIFICANCE OF CONTEMPORARY DISCOMFORTS AGAINST THAT AMOUNT OF HISTORY COMFORTS ME.”

Although I’ve never been as cool as the kids who flock to his shows in head-to-toe Jedi, Owens has meant – and continues to mean – the world to me and to my fashion life. As someone who shares his sensitivities to the relationship between the real world and this dream world of ours, through the years he has become my Seasonal Jesus: someone to hear my prayers, someone who cares. I know that fashion reflects and affects its surrounding world. I know it’s a force for change. And I have no qualms justifying the industry I work in. But once in a while, amid the selfies and poses and street style and air kisses, it’s comforting to hear his words of wisdom – ever so poetic, philosophical, astute. I’m a smarter person for knowing him.

In January, all he could think about was Ukraine. “I look around and I see things and I cringe a little, thinking, they know there’s a war going on, right? I realise, also, that we are companies that need to be on the top of our game. We represent the very best of this kind of industry and people expect excellence. We have to deliver that. We can’t ignore that. But there are ways of delivering that excellence which aren’t quite as voracious and conspicuously consumptive.” Last year, he was feeling the weight of the reactionary social climate: “It’s getting worse. On every New York Times story, the comments always disintegrate into bickering: people needing to be morally or intellectually superior to someone who wrote something else. No matter how benign or gentle the story is, people always descend to disgusting comments, which is bigotry.”

These quotes are representative of any conversation I’ll have with Owens today. Whether it’s over dinner, backstage or in emails, I consider him a kind of messianic therapist. I earned my Owens education in the “bunker in Bercy”. It’s how he used to refer to the grass-covered omni-sports arena which hosted some of his most memorable shows. Back then, it was a different kind of theatre: there was the SS13 show for which he covered the floor in foam; there was the SS14 men’s show with a performance by the metal band Winny Puhh, who were suspended from the ceiling; there was the SS14 women’s show modelled by a formidable American high school step team.

One of my favourite soundtracks ever still comes from that Owens era: Ima Read by Zebra Katz, which scored his AW12 women’s show and created one of the most brutal meta moments I’ve experienced in a fashion show (perhaps only outdone by Karl Lagerfeld’s supermarket show for Chanel, which ended with guests running to the set to get their hands on the material goods). “Ima take that bitch to college, Ima give that bitch some knowledge. Ima read, Ima read, Ima read,” it went, over and over and over again. It was stunning.

But in 2014, something changed. Owens moved his shows to Palais de Tokyo, the monumental, art deco masterpiece on the River Seine. Here, the evolution of the philosopher I know today would truly begin to unfold. Slowly, his gestures became more poetic. It was here he staged a show modelled entirely by his team, where he casually put penises on display (“You know I love a simply tiny, little gesture that packs the wallop”) and where he staged my favourite ever display of wisdom, for his SS18 men’s show. From the roof of Palais de Tokyo, in the scorching summer sun, descended the most exquisite dark tailoring like black angels falling from the sky in majestic gazar, cloqué and duchesse.

“In this time of hate and pain, we need a remedy. I need a freak,” said Owens after the show, citing the Sexual Harassment soundtrack that defined the show. And then, he said something I’ll never forget: “A freak to me is something rare, sensational, inspired by the unusual. And I’m seeing this normality in the world that’s kind of being lionised and deified, and personally that’s my refrain: I need a freak in life. I need to be surprised. I need effort. And I need things to be rare and not banal. Celebrating the prosaic and conventional is amusing but it’s not the spirit of my spirit. It’s a little mean-spirited. A little snotty.”

To me, those words still capture the essence of my love for Rick Owens, both the brand and the man. As a fashion phenomenon, it is entirely its own: an institution at once familiar and completely strange; a safe haven for abnormality, honesty and beauty. As an individual, he is like no other human I’ve ever met, the rarest, most different and most uncompromisingly genuine person to hit this planet; an arch freak, who puts every bit of his heart into making the world a better place for people who think, behave or indeed dress differently than the norm. Through that lens, he’s a kind of beacon: a fashion constant to light the way. In my eyes, he’s certainly way up there with Karl and his kind.

Portrait by Danielle Levitt. Issue 21 of 10 Magazine Australia is on newsstands now.