LUELLA BARTLEY ON RECONNECTING WITH THE BODY THROUGH ART

Are you sitting comfortably? Try to find somewhere that feels good to you and let’s try something. Begin by feeling your seat’s surface, then your feet grounded on the earth. Take a deep breath, then slowly release it. Do it again. What comes up? Some might find this mindful, dropping pleasantly into a grounded state; others might feel their thoughts circling, a sense of feeling unsettled slowly seeping in.

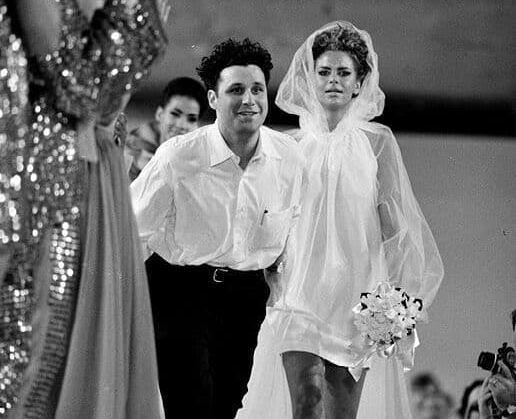

Being “in our bodies” is not something we draw attention to particularly often, nor is it called upon at unconscious moments to regulate ourselves or when we’re being guided, for example, during a yoga practice. The phrase feels flawed. After all, our head is a part of our body. However, it can be uncomfortable to drop into the physical self instead of the thinking mind. A resistance that is inevitable when so much of contemporary life is orientated towards using something to escape ourselves – technology, alcohol, drugs, food and even, for some, fashion. The acclaimed fashion designer Luella Bartley, who was awarded an MBE for her contribution to fashion in 2008, has, in the past, felt more comfortable in her head. “Usually, I’m overthinking everything,” she says. “I got to a point in fashion where I’d never use my hands. I didn’t draw, I didn’t sew. As a creative director, I was conceptualising all the time.” Over the past three years, she has been practising as an artist, making paintings, line drawings, photographs and sculptures, reconnecting with her body using her hands. “It started as a therapeutic practice. I went through a lot of shit, so I began with clay. There was something about getting my hands dirty. I went to a different place when I was drawing, sculpting or painting – it is physical, not mental.” Her journey towards art began to crystallise as a direct result of the illness and sad passing of her beloved son, Kip, who was only 18 when he died in 2021 of leukaemia after an illness lasting two and a half years. In an interview with the Observer in July, she related how her life was upended. “College, career, different careers, children. I don’t think I stopped to reflect. Obviously Kip getting ill was a real stop sign for me. It was full of the most…” She takes a moment, floored by sudden tears, “…the most terrifying and powerless feeling in the world. But he – it – taught me so much. I don’t think I can put it into words, it’s only been two years, and I’m still reeling from it, but so much has changed, internally. I’m a sadder, but braver and more solid person.”

In the paintings she makes now, which she calls “sketches in oil”, female bodies undulate, with large-scale parts of them elongated or exaggerated. They are dynamic. They tussle and push like they are figuring something out. It is as if, in a subtle, surreptitious way, over time, they will burst from the canvas they are entrapped in.

The artwork is the result, but it is the process that is incendiary. “I don’t think about my body and the physicality and emotion of being a woman a lot in this work. It’s more instinctive. I’m getting a kick out of repetitively drawing the female form, painting the female form, photographing the female form,” she says. “I can’t explain it, but it’s definitely had an effect on me as a woman. It’s been a process that’s made me pay attention and find comfort. It has made me feel more grounded, more inquiring. It’s helped me make decisions in my life that have been brave. Energy has transferred from the work into me.”

The first body of work that Bartley exhibited at London’s Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery in the summer of 2022 was about tension and anxiety, exploring vulnerability, intimacy and conflict around the female experience – “almost like the ugliness of being a woman being looked at as a woman”, she explains. Her new work eases into this vulnerability, sloshing around it, confronting it, revelling in it. She has found it a route to a truer connection. “The more open you are about yourself, the more you attract people who understand you. In the work I’m doing now, there’s a lot less tension. It’s more about how I see that vulnerability as a strength.”

The authenticity in the process and drawing on lived experience are what make her work so compelling. When I view it, the cogs in my mind whirr as if the bodies are a Rubik’s cube, and when they are slotted together in a certain configuration, something might eventually be worked out. What is it to be women in our bodies? We are obviously in our body, we own it, but in many ways we don’t. We might capitalise on it, use and abuse it, or others might abuse us, and we are the victims of this. We might love ourselves fully and tenderly, caress our bodies and care for them. Or we might disassociate, where we are outside ourselves, looking on and wondering: who is that down there? Surely not me?! It is not a singular experience. Bartley is drawing solely on her experience, but I resonate with her as she speaks. She tells me, “This is the only time, the first time, that I am really inhabiting my body – I was completely disconnected from it. I abused it in my teens and twenties. I had such a negative relationship with it. I had a personal experience that made things difficult, but I’m sure there were some social aspects to it. I suppose the first time I felt my body was when I had kids and I was pregnant, which is a very different kind of thing to what I’m thinking about now.” I ask about the role that shame plays in her work. “The process is not necessarily understanding the shame that I’ve felt through my life,” she says, “although it has been a process of stripping it away and becoming more celebratory about it. And it’s not even about the physical body, it’s about how you feel about being female. In my teenage years, I was terribly ashamed of everything.” This curiosity has led to an investigation reverberating throughout the work, asking: “Was that just me? Is that how every young girl feels? Why is that?” She continues, “I don’t like the word ‘objectified’, but just being looked at, judged, picked at, made me feel uncomfortable. So I completely disassociated.”

To make her most recent body of work, Bartley began by shooting a nude female model, then developing them into oil sketches, layering on her own experience instead of simply presenting the body as it appeared. Throughout, she worked with one model, Esther. “It’s interesting working with Esther because we have a different view of women’s physicality and sexuality. I’ve felt quite repressed, oftentimes embarrassed and shameful, quiet and hidden. And she’s the opposite.” It is these generous conversations with other women that push the work forward; when shooting the images for this piece, Bartley described how Vanina Sorrenti invited her to get out of her comfort zone. “She got me moving my body and writhing on the floor, legs in the air, and it felt really good to have that trust with her.” It has been revelatory how the art has encouraged new relationships to form. “When I started doing this, I had different conversations. You let your guard down and attract the people who understand what you’re trying to do.”

The process of doing the work has brought Bartley to a new place. “Now is the first time I’ve had the freedom to think about what my body means to me, as an autonomous thing, physically, sexually. It’s mine again, I inhabit it. It’s there to be explored, understood and given attention, because I never did. It’s always been about the mind and the brain for me.” The power and transcendence in this approach cannot be underestimated. She has given herself permission to explore her own body in ways that haven’t felt available. I ask whether she’ll venture into self-portraiture. “I know I need to do it. The process confuses and terrifies me. It’s that little step I haven’t got to yet. It’s frightening. But that fear is definitely to be explored.”

When we speak, Bartley has just celebrated her birthday. Upon turning 50, she describes feeling more powerful than she has ever felt in her whole life. She tells me that there is a profundity in looking at the work she has created because she never intended to show it to anyone. I offer that she might one day feel comfortable drawing her wrist, shoulder or foot, before telling herself that she will never show it to anyone. Then, over time, she might feel curious about what conversations she could have if she were to give another person a peek. I think of the figures she draws and see a parallel. It is as if Luella Bartley is slowly, meticulously, working her way through the canvas hat once entrapped her.

Photography by Vanina Sorrenti.