Ten Meets Pierre Hardy, Hermès' Jewellery Extraordinaire

“I was not attracted by jewellery, it wasn’t something I’d longed to do. I would never have dared to do it by myself.” This was not the answer I expected as I began my interview with Pierre Hardy, 68, the creator of ultra-sophisticated, self-assured and daringly conceptual high jewellery collections for Hermès. I had asked Hardy how and why he was drawn to jewellery, which had both diverted from and added to his role as creative director for men’s and women’s footwear at the maison since 1990. It was, he explains, the idea of Jean-Louis Dumas (the late chairman and artistic director of Hermès), who clearly saw jewellery as a natural next step for Hardy. “He seemed so sure, it was so obvious to him that I had to do it,” the designer explains. “I was an absolute beginner, so for me it was more about curiosity, experimenting, asking myself questions. I tried to treat jewellery as personally and subjectively as possible.”

Hardy embarked on gems for Hermès in 2001, starting with silver fine jewellery, by learning how to transform metal into the shapes he envisaged. Having worked for the maison for some years, he says, he had had time to “embrace the Hermès universe”. He adds, “I tried to use what I knew about Hermès, to think about what I would have loved to see in Hermès jewellery myself. It was a good moment, a good feeling, to draw on my experience and yet have no boundaries. [To get] the opportunity to experiment with this new field of creativity, another completely new métier. It was like discovering a new atelier, new techniques, new studios, new materials.” For his first silver collection, he translated recognised Hermès elements – the chaine d’ancre and clou bracelets, the Kelly bag, the lock, even their dog collar – which gave him the chance, he says, to start step by step and progress slowly to high jewellery.

Hardy’s first high jewellery collection for Hermès, Haute Bijouterie, was launched in 2010, with the Fouet, a slinky, tactile, diamond-smothered, entwined, rope-like necklace in the form of a whip, and the Centaure ring, a powerful graphic interpretation of a horse’s hoof, both referencing Hermès’s equestrian heritage. Since then, however, through increasingly complex concepts and sophisticated techniques, he has been steadily building a whole new visual vocabulary for Hermès jewellery, finding new and relevant creative expressions for what he sees as one of the earliest of art forms. “Jewellery is an old world reaching back to Mesopotamia. In more recent times, it has become so classic, so traditional. My aim is to try to bring something different, to propose new shapes and forms, a new approach.”

Hardy says that while the extreme preciousness of materials and the jewels’ inbuilt longevity, an heirloom syndrome which set jewellery far apart from a fashion accessory, he applies the same design and drawing process he employs for other objects. Shoes, for example, he says, for which he is perhaps most celebrated, demand precision of shape, form and fit, even if jewellery demands “1,000 per cent more”. Both are connected to intense femininity. “The way I think about the woman at the moment of creation is very similar.” He explains that, as with all his design work, his high jewellery concepts are the result of his training and experience in fine art and fashion.

Having graduated with a fine arts teaching degree from the École Normale Supérieure, he joined a professional dance company, then taught dramatic arts and applied arts before working as an illustrator. That brought him to the attention of Dior, who he designed shoes for from 1987 until he joined Hermès in 1990. In 1999 he launched his own brand, creating women’s and men’s shoes, handbags and trainers. His work with Hermès has bred contemporary classics like the Oran sandal, the leather trainer that was the first to be launched by a luxury brand, and the Hermès Apple Watch. Hardy is known for his versatility, eclecticism and powerful graphic style, which is influenced by architecture and conceptual art, design, cinematography, scenography, movement, cars and much else. This unstoppable curiosity has led him to a series of varied collaborations with Balenciaga, Gap, Frédéric Malle and Nars. He also designs the jewel-like packaging for Hermès’ beauty products. His work is the sum of all he has experienced, learnt and loved. It’s instinctive, automatic, he says, “I don’t know any other way.”

Learning about jewellery was like learning the notes in music, then putting them together and creating harmonies, hopefully entire symphonies. He came to understand that jewellery has a special status in the world of design and also an intimate relationship with the body. This fascinated him: Hardy’s mother was a ballet teacher and his own background in dance taught him the importance of learning how to use and master the body, how to make it look better. As he developed his ideas, he became more and more aware of the way in which a jewel moves and interacts with the wearer. Just as there are different kinds of femininity, so some women, he says, want the jewel to feel heavy, substantial and reassuring. While others prefer it to feel light, like a second skin. “I learnt how to integrate all of this into pure design. I understood that the jewellery experience is very personal and revolves around how a woman feels when she’s wearing her jewellery, how it makes her look and feel, perhaps stronger, better. I loved it!”

Yet, visual pleasure is also vital, “Shape is very important to me,” he says. After Fouet and Centaure, Hardy began experimenting with more radical ideas to imagine an entirely new way of translating Hermès’s style and story. “Everyone has an image of the typical Hermès vocabulary. I wanted to bring it to life, perhaps invent new words, new shapes, a new way of integrating the Hermès universe.” The daringly contemporary Lignes Sensible collection was billed as a “manifesto of gracious radicality”. It marked Hardy’s growing confidence in experimenting with concepts connected to art and architecture, and to his preoccupation with the jewel’s connection to the body, emotional and physical. Through dynamic lines, reminiscent of the human sensory system, Hardy gave form to invisible waves of energy, like faint sketches on skin. He chose muted, watercolour-like gemstone hues, pastel tourmalines, sapphires and soft green prehnite. In contrast, Les Formes de la Couleur, his new collection, centres on an exploration of colour, on the relationship between colour and form, drawing on the vibrations of different colours to energise line and volume. Hardy dipped back into his fine art training, referencing colour theory and using coloured gems like paints to create powerful, yet sensual compositions of pure form, line and colour. “It was very new for me to use so much colour, to express the idea of colour in the strongest and most interesting way.” It was also a way to reference the signature rich colours of Hermès’s silks.

One of his main challenges has been to do justice to the beauty of the precious materials at his disposal. “From the beginning I found the materials beautiful. The stones are amazingly beautiful, the metals amazingly precious and beautiful. I knew I had to find ways to make them more beautiful to enhance the beauty of nature.”

For Hardy, the light that is the soul of a gemstone, as the lustre of metals become materials in their own right. In Les Jeux de L’Ombre, he has played with contrasts of light and shade, using titanium to give form and opacity to ephemeral, shifting shadows, suggesting the secrets that hide in them. It was a way perhaps of subverting the traditional ‘sparkle’ of a jewel, while also referencing the shadows thrown behind spotlights on a stage full of dancers.

I suggest that his high jewellery collections, underpinned as they are by complex ideas, are unusually cerebral, which surprises and slightly alarms him. He hopes his jewellery is also sensual and sensitive, not too intellectual. There is that sensuality, along with playful wit, light and lightness, in his 2022 Kellymorphose collection. In it, he reinvented the signature details of the Kelly bag: the trapezoid shape, lock, straps, key and clochette keyholder. He used the graphic modernism of the baguette-cut diamond to create his own signatures: graphic lines, architectural form and body-conscious dynamism. It is the perfect illustration of what he calls the dialogue with Hermès. “It is like a duet, aiming to reach harmony between what I love and what Hermès needs to express. I enjoy it a lot!”

Finally, explaining how he creates high jewellery collections every two years, he says that the length of time required to fabricate jewels feels like an “escape” from the demands of fast-moving, continually-changing fashion. It’s the perspective of time that changes everything, as it allows him to revisit and reinvent motifs and patterns, rather than chase something new. It allows the endlessly versatile and curious Pierre Hardy to bring true design excellence, intelligence and contemporary context to the time-honoured, age-old art of the jewel.

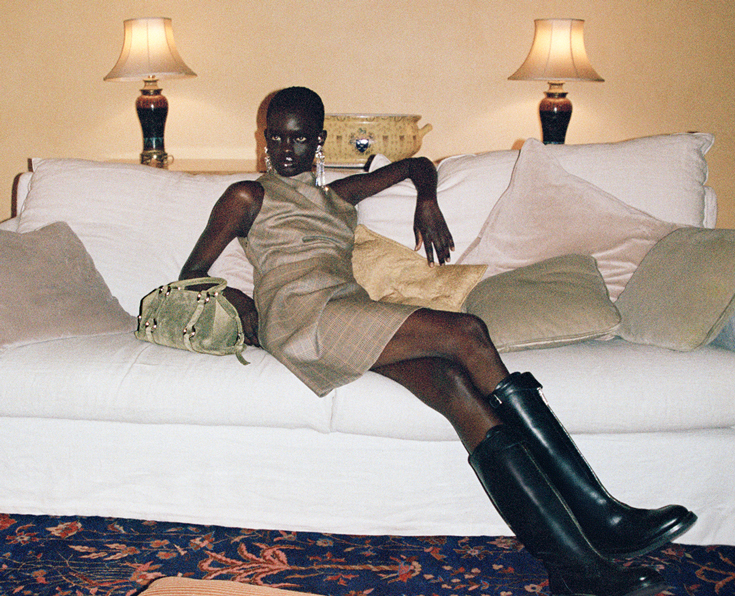

Photography by Harley Weir and Guido Mocafico, courtesy of Hermes. Top image: photography by Brigitte Lacombe. Taken from 10+ UK Issue 7 – DECADENCE, MORE, PLEASURE – out NOW. Order your copy here.