LOUIS WISE ON THE ART OF THE FRENCH EXIT

So many questions around freedom. When I think of it, I think of the French Revolution, of Nelson Mandela, of, umm, George Michael; I think of wars which reappear on our doorsteps, or of laws suddenly created in a crisis. Freedom comes and goes. I suppose I’ve broadly had it in my lifetime, but with the usual caveats: free to do certain things within the norms of my identity, gender or caste. Free to live a semi-free life, which I think is really only what most of us can ask for. But there’s one liberty which has long troubled me, and which possibly reveals the extent of my very serious problems. When are you free to leave a party?

Whenever I’m invited to a soirée, a question soon appears at the back of my mind: when will I be able to go? It’s not that I’m looking forward to it – broadly, I’m fine with a social, as long as there’s good booze and good dancing (warm prosecco, career chat and huddling in awkward groups, less so). But I immediately wonder how much this event will take out of me. What is my required input? What does the host need to have a good time? Or, to rephrase it more honestly: how much of a fab friend do I have to show myself to be? Though a party is often sold as a celebration, I tend to view it as something heavier, more binding, a ritual which confirms the relationships I have and the value they have to me. I mean, sure, I’ll roll around under the tables, but there’s always been a slightly serious, moral component to my attendance, especially when it’s for a birthday, a wedding or an anniversary. I’ve also automatically assumed I have to get home completely destroyed on cheap wine, ciggies and shots: a small evening sacrifice of my health, an offering to the gods of #AboutLastNight.

Just the other day, in fact, I was at a mate’s thirtieth and, even though I was having a lovely time in this Dalston basement, eventually I thought: I’d quite like to go now. Somehow, though, I couldn’t. As my friend swished around the dance floor, there was no point in lying to myself: she’d be perfectly fine without me. Getting an Uber home at ten past midnight was hardly going to ruin her night. And yet I couldn’t visualise doing it, and I certainly couldn’t face saying bye: it seemed almost catastrophic. So I stayed and stayed – mostly having fun, I should add – until the inevitable happened and she came up to me and said, “I think I might go, is that okay?”

Since we were now on our third consecutive Kesha song, this seemed understandable. But as soon as she said it, I felt played. She had made the decision, and suddenly I was one of the last ones left. More to the point, she was freer than me.

I’ve always felt this way. One side effect is that I’ve also always been very rude about people who leave parties early, which is to say, pretty much anybody who leaves before the end. As far as I’m concerned, people who don’t stay until an event is left in embers have failed it. I still remember the pal who left their own birthday party at 10pm while the rest of us stood around wondering why we’d been summoned to this grotty bar in Shoreditch (actually, there’s no point in pretending to be snobbish about that – I was always in a grotty bar in Shoreditch). Their exit was pretty gauche, nigh-on rude, but I didn’t leave it at that. To my mind, it was a perfect example of how lacking this friend was in other departments. How poor a friend they were, as opposed to, say, me. But now, as I’ve gotten older, I wonder if it has less to do with virtue and more with jealousy. I was livid they felt entitled to leave.

Why don’t I go earlier? I suppose it’s a fierce mixture of FOMO and virtue-signalling, mixed with the uncomfortable feeling that I don’t know what to do with my own freedom. It just stresses me out, so I defer to what the party dictates. (To be clear, when a bash is completely dull and dreadful, I do leave, but that feels like a principled decision, coupled with basic survival instincts.) My reluctance also has to do with the romance of friendship and an unwillingness to ever let it die. The most shocking thing my therapist ever said to me was, “Have you ever imagined being free?” It shut me up immediately. And then I nearly laughed. I thought it was such a basic and silly notion. Being free is the kind of thing you can chant about in pop songs – hi Ultra Naté! Hi George! Etc – but I’m never sure how it applies to day-to-day life. There is too much present to check our freedoms; often for better, I think, if sometimes for worse.

In the case of leaving parties, it implies a choice – a choice to say, “Thank you, this has been nice, but I’m going to do my own thing now.” It spells out: my pleasure is just a little bit greater than yours. It also keeps bringing me back to a phrase that I’ve long had in my head: you don’t want to be the last person left at a party. I don’t know where I first heard it, but for some reason it has stuck. Yet it’s not so much been something I’ve dreaded in real terms (if the lights come on and you’ve sung the last song, then fine: at least you’ve got your money’s worth) but in broader, less literal ones. I’m 39 now and, without wishing to sound overly glum, you could say that my entire thirties have been characterised by people slowly but surely leaving the party. Some have got married and had kids; some have moved abroad; some have stormed off because they didn’t like the music (yes, this is a metaphor); some, almost more painfully, have just drifted off to other parties (metaphor again). When I was growing up, I had an intense phobia of being that one slightly older person who didn’t know when the jig was up; the one who still wanted an extra drink, who still told the same old anecdote. It’s a sign of maturity – of sophistication – to know when to leave a party, right? And this time I mean that both literally and metaphorically. And yet, to my own embarrassment, I still don’t quite feel free to do it.

This obviously has to do with being mostly single, no kids, maybe even having a job which quite likes me going to parties. It has to do with my reasons for leaving not quite seeming valid enough to me and maybe even to others, even though they surely are. (Currently these do seem to boil down to “sleep” and “a regular skincare routine”, but I reserve the right to acquire more.) But actually, I’m now standing up for them, if only because otherwise I’m just living by everyone else’s decisions, night after night after night. And this isn’t, it turns out, an amazing yardstick for friendship, though for a long time it maybe seemed like it.

Another party, a few weeks ago: a big gathering abroad for three days and nights for a close friend’s fortieth. A whole afternoon and evening’s drinking on the first day and, at midnight, I thought: I have to get to bed. Everyone was still going but I got up to get a glass of water, then took an abrupt right turn and snuck off to my room. I kept telling myself this was fine, but it didn’t really feel like it. As I shuffled silently down the Airbnb chateau’s corridor, being sure to not turn the lights on, it felt like a betrayal, a crime. If it was, it wasn’t because I was doing what I wanted, but because I didn’t quite have the guts to say why, which surely is something a loved one deserves. The courage to say to a friend: “I love you, this has been great, but it’s time for me to make a move. This party, for me, is over. Listen, don’t panic, you’re only 40, babes! There’ll be more. It’s just that I don’t want to be here right now – I can’t be.” It’s dumb, obvious, but I guess I’ll be properly free when I can live with saying goodbye.

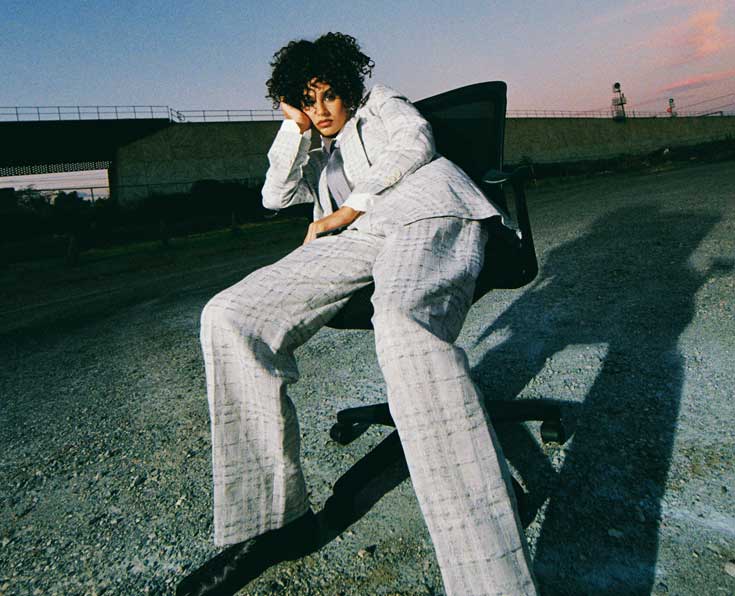

Photography by Derek Ridgers and styling by Garth Allday Spencer.